Trade and the Farm Economy-Two Charts to Watch in 2020

Before the ink dried on the newly signed Phase 1 trade agreement, dozens of articles and Twitter threads emerged with clever insights into the nuances and subtleties of the agreement. Most debates focused on the base level China agree to buy up from, and the relevant commodities and products. Stepping back from the details, this week’s post considers the potential impacts and implications of trade and the farm economy with two charts.

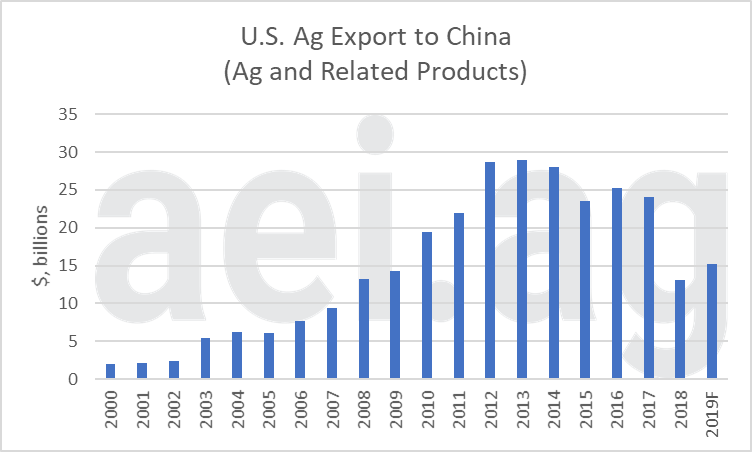

U.S. Ag Exports to China

The question on everyone’s mind is how China’s purchases of U.S. ag products expands over the next few years. Figure 1 shows U.S. exports of agricultural and related products to China[1]. Again, the goal here is not digging into the Phase 1 trade deal specifics, but rather looking at historic trends.

China’s purchases peaked at nearly $29 billion in 2012 and 2013. Exports to China, measured in dollars, peaked when commodity prices peaked. This isn’t a coincidence. Measuring trade activity in dollars is beneficial because one can aggregate across commodities and products, but is limiting as year-to-year changes could be driven by changes in 1) volume and/or 2) prices.

During the Trade War, trade activity with China contracted sharply. China’s purchases in 2018 were 45% less than 2017 levels. Forecasted 2019 levels were 37% less than 2017 levels.

Without a doubt, the best outcome from Phase 1 is the possibility of U.S. exports to China returning to pre-Trade War levels.

Figure 1. U.S Export to China – Ag and Related Products, 2000 to 2019F. Data Source: USDA’s FAS & aei.ag calculation.

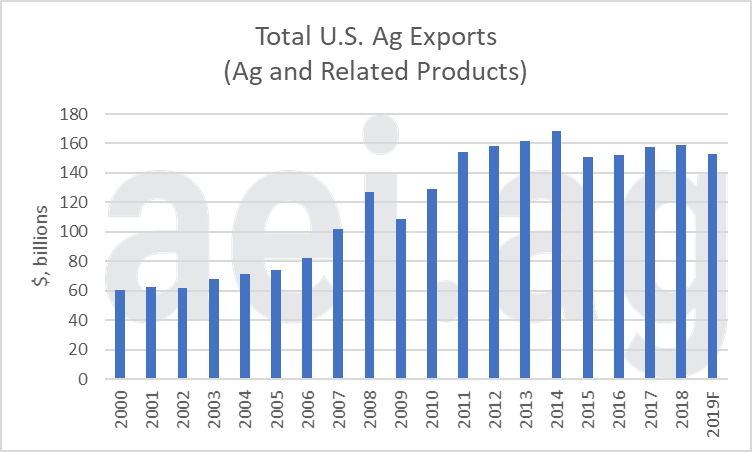

Total U.S. Ag Exports

The second – and perhaps most important- chart to consider is total U.S. ag exports. In recent years, total U.S. exports of ag and related products have ranged between $150 – $160 billion. Trade activity has contracted from the highs of $169 billion (2014) but has remained strong in recent years.

Often overlooked in the discussion about the future of trade with China are the implications for total exports. If there is a surge in China’s purchase activity – say ag exports (as reported in figure 1) surge to more than $30 or $35 billion in 2020- would that, in turn, move the needle on total U.S. ag exports?

Consider the scale of China’s purchases. In 2017, China accounted for 15% of total U.S. ag exports. While China is a significant, important trade partner, the U.S. ag export markets are, overall, diversified. The three largest buyers of U.S. ag exports– China, Mexico, Canada – accounted for 54% of total activity in 2017.

As a result of the previous point, the relationship between China’s buying activity and total U.S. ag exports is tricky. In 2018, when China’s purchases fell 45% (or $10.8 billion), total ag exports increased by 1% ($1.7 billion). Most recently, China’s purchases in 2019 are forecasted to be $8.8 billion below 2017 levels, while total exports are forecasted at $4.8 billion below 2017 levels. This is to say the global trade economy adjusts. In 2020, if China steps-up and buys more U.S. soybeans, the U.S. will probably lose sales to non-Chinese soybean markets. Taken one step further: if China’s purchases of ag and related products exceeded $35 billion in 2020 (figure 1), how does the $20 billion increase translate into total U.S. ag exports (figure 2)? It is unlikely to have a dollar-for-dollar impact.

Figure 2. Total U.S. Ag Exports – Ag and Related Products, 2000 to 2019F. Data Source: USDA’s FAS & aei.ag calculation.

Wrapping it Up

An easy way to think about these two charts is a pie. Figure 2 represents the total size of the pie, while figure 1 is China’s slice (or share). While China has agreed to purchase more U.S. ag exports, the overall implications are unclear. Will the terms of Phase 1 translate into China account for a larger slice of the current pie, or does the pie get bigger? In other words, how much of increased purchases from China would represent reallocating existing trade activity versus new global demand?

Again, the Phase 1 trade deal is a positive development. That said, there are unknowns. In addition to questions and skepticism about China’s ability to meet its purchase commitments, it is also unclear how additional purchases would impact the U.S. farm economy. If the majority of China’s new purchases are a reallocation of current trade, impacts would be limited. Should new purchases represent new demand, the outcomes would be much more favorable for the farm economy.

It is entirely possible for China to significantly increase its purchases of U.S ag products while total U.S. ag exports remain mostly unchanged. On the other hand, it is also possible for China’s purchases to modestly increase but result in a meaningful increase in total ag exports. These two scenarios would, of course, have different impacts on the farm economy.

In short, Phase 1 is positive news for the farm economy. That said, it is important to remember the farm economy is dependent on trade with several countries. While ag export to China (figure 1) is a popular topic in 2020, it is important to note lose sight of total exports (figure 2).

Click here to subscribe to AEI’s Weekly Insights email and receive our free, in-depth articles in your inbox every Monday morning.

You can also click here to visit the archive of articles – hundreds of them – and to browse by topic. We hope you will continue the conversation with us on Twitter and Facebook.

[1] Agricultural Related Products include ethanol, biodiesel (and biodiesel blends), forest products, fish products.

Source: David Widmar, Agricultural Economic Insights